Anna Forés Miravelles (Barcelona, 1966) holds a degree and PhD in Philosophy and Educational Sciences from the University of Barcelona (UB). She is passionate about education and has a firm belief in people’s potential. Her research focuses on education, didactics and innovation in different learning environments.

Jordi Grané Ortega (Sabadell, 1962) holds a degree in Philosophy from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and a master’s degree in Sociology and Public Management from the same university. His professional and academic career has focused on promoting coexistence and conflict resolution, political consultancy and resilience.

With greater or lesser conviction, education is generally accepted as the driving force for change in society. Perhaps it is a kind of mantra, but some not only believe it but also subscribe to it and give it meaning through action. The authors of this book forge the verb “resilient” to apply it to education and make the ordinary extraordinary over a transformation through education. A contribution to enriching human life through education. (p. 11). Thoughts that may provoke actions. The goal is to face two challenges: educating to cope with uncertainty, volatility and complexity and educating to reverse fatality or the absence of alternatives. (p. 12)

Thoughts that provoke action to face two challenges: uncertainty, volatility and complexity and to reverse fatality or the absence of alternatives.

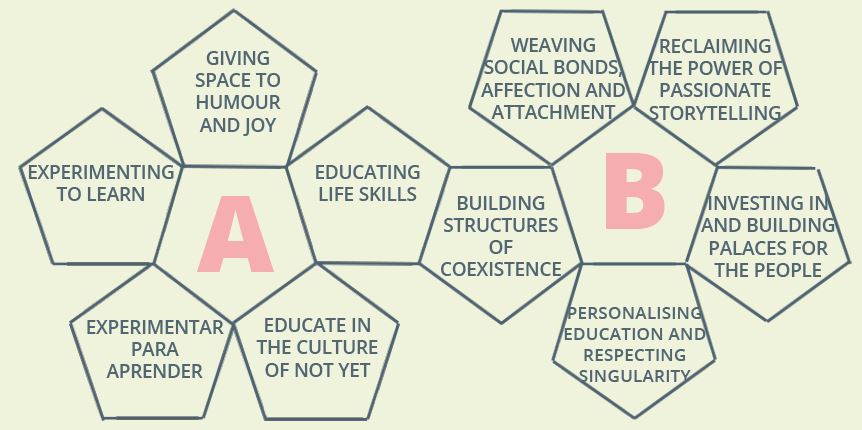

Forés and Grané propose 60 strategies to promote educational resilience distributed in two core generative actions (G6 and C12) on which five others depend. The first six refer to self-growth, and the other six refer to developing the “we-others”. Their humanistic vision of the world makes it become a better place to live if we turn our thoughts into resilient actions, i.e. actions that can be put into practice in real-time in our classrooms.

A glance at the summary can help us get an idea of the content and the level of commitment the authors encourage us to:

G1. Make room for humour and joy. Generate playful attitudes, happiness and optimism.

G2. Educate life skills. Generate a meaningful, accessible, improvised and humble life.

G3. Educate in the culture of “not yet”. Generate a growth mind set, room for error and challenge, motivation 3.0, wise praise and grit

G4. Experiment to learn. Generate appropriate learning rhythms and times and a broad, original, curious and creative mentality.

G5. Learn to be and become. Generate up-to-date data, effective thinking, introspection, agility and autonomy.

G6. Perform executive functions. Generate attention, flexibility, inhibition, planning and sound decisions.

G7. Weave social bonds, affection, attachment and security. Generate relationships of authenticity, limits, care, conversations, compassion and kindness.

G8. Personalise education and respect uniqueness. Generate alternatives, opportunities, potential and beauty.

G9. Recover the power of passionately storytelling. Generate friendly languages, agoras, questions and vocabularies of hope.

G10. Build structures of coexistence. Generate moral imagination, the third side, the excellent use of memory and forgetting, and forgiveness.

G11. Invest and build palaces for the people. Generate teal organisations, self-management, wholeness, purpose and democracy.

C12. Expand the definition of “we-others”. Generate rebellion, cooperation, community, change, future and the transition from ego culture to eco culture.

Grané and Forés had addressed this issue of resilience in previous publications. In La resiliencia. Crecer desde la adversidad (Plataforma, 2008), it was approached as a response to adversity. In contrast, in Los patitos feos y los cisnes negros (Plataforma, 2019), they called it “generative resilience”, understood as “the art of generating opportunities from uncertainty”. If we find ourselves in a society where change is the natural way of life, what is the most appropriate approach for schools to take with their students? The authors are committed to thinking that leads to action, taking into account the realities and possibilities of each school. Therefore, it is not a methodology or a systemic application of what could be called a resilient curriculum

The model they offer is based on the geometric figure of the dodecahedron, made up of 12 pentagons, which makes it possible to describe five strategies for each action, which, duly combined, become the 60 proposals that can facilitate resilience. A way of making a complex issue visible through a simple image. Resilience is a construct, and therefore it isn’t easy to measure its degree of achievement. Nowhere have I seen the authors link the success of their proposal to the need to implement it fully. It is, in my opinion, a virtue of the model: its openness and flexibility. The more strategies that can be implemented, the more consistent the generation of resilience in education will be.

The reading is pleasant and stimulating: there is a succession of numerous current authors with very successful quotations from their works and multiple examples that, on the one hand, seem to lead you to lose the common thread of the work, but, on the other hand, it is precisely this diversity of options that makes Grané and Forés’ proposal accessible and worthy. The descriptions of the strategies are followed by proposals for educational activities that exclude the imperative mode and become, for this very reason, invitations not to miss the opportunity to try to apply some of them, starting with the next hour of class.

I cannot overlook the opportunity to briefly reproduce some of the authors’ thoughts in this book. They may seem to be simplifications or advice typical of self-help manuals. Still, in reality, they are commitments that each person can take ownership of, whatever place they occupy in the educational system. Therefore, it does not depend on the global implementation of a model but the attitude and each individual disposition. To make it possible is also to want to make it possible. Let us look at some of them as inspiring examples:

“Our brain likes pleasure, so if the learning situation is related to joy, we will tend to repeat it. When we are proud that we have succeeded in solving a problem, meeting a challenge, we also feel joyful about learning”. (p. 24-25)

“The primary human motivating force is to find meaning in one’s life”. (p. 30) “To educate is to humanise in order to transmit sense. Therefore, any pedagogy of meaning must guide students to equip themselves with this vital project necessary to live a meaningful life”. (p. 31)

“To educate is to put humility in the little things […]: a smile, a kind word, a gesture, a caress, attention, a moment, etc.” (p. 35)

“Excellent teachers are the ones who encourage intellectual development because they believe that intelligence is flexible and malleable. They are growth-minded teachers”. (p. 37)

“Educating involves developing a culture of challenge that prepares the learner for the journey, not the trip for the learner”. (p. 41)

“We must slow down education and the pace of learning, and we must avoid standard, uniform and rigid rhythms for all students and give greater importance to learning done in-depth. […] It makes no sense to teach only to prepare students to pass standardised tests”. (p.50)

“Let us never forget that a world where the action is guided by practical and critical thinking enables to educate and activate free citizens”. (p. 61)

“The absence of limits is also a form of child abuse. Educating is an uncertain art where setting clear and firm boundaries is an expression of love”. (p. 81)

“We must personalise education because we are all unique and unrepeatable cases, and we learn in different ways”. (p. 89)

“We have to change the deficient educational model for the generative educational model. The basic assumption of the generative mentality is that it is always possible to find in a student what works well”. (p. 93)

“The resilient educational coach is a narrative and cultural coach who uses the power of kind words to generate collective vocabularies and reports that contribute to creating a protective and affective bubble for students”. (p. 99)

“Teachers are more used to giving answers than to provoking questions from students. But educating involves learning to ask good questions”. (p. 103)

“To have a soul, schools need to enable the individual and organisational purpose to resonate and reinforce each other. […] This happens when educating meets the teaching vocation”. (p. 123)

“Learning from the future as it emerges involves creating the world anew; learning from the future consists in accepting high levels of uncertainty; it involves opening ourselves to the unthinkable and, at times, doing the impossible”. (p. 134)

In short, it is a book recommended to parents, teachers and educational administrators with a growth mind set and an optimistic vision of what can still be done to promote generative resilience in education actively.

You might also like

Leave A Comment