by Ana Moreno Salvo

Francesc Torralba Roselló holds a doctorate in Education, Philosophy, History and Theology. He is currently an accredited full professor at Ramon Llull University. He alternates teaching with writing and disseminating his thoughts. His work is geared at philosophical and ethical anthropology framed within contemporary personalism. He is a prolific author, with more than 1,800 articles and 100 books published, including: “Vivir en lo esencial” (Plataforma Editorial, SL, 2020), Liderazgo ético (Ppc Editorial, 2017), “Correr para pensar y sentir” (Lectio, 2015) and “El valor de tenir valors” (Ara llibres, 2012).

At Impuls Educació we are interested in international research and we try to establish connections with experts from all over the world. We consider it essential, as a research and dissemination centre, to take into account the opinion and experience of these professionals, whose vision always provides us with new perspectives and ways of understanding this exciting world of education.

Interview with Francesc Torralba

Recently, educating for civic awareness, democratic values, social justice and sustainability has been considered basic. You have dedicated a large part of your life to reflecting on the human person and its development. Could you explain to us what does it mean to educate to be and what is its main purpose?

To educate, especially in an education centred on being, actually means to develop all the powers or capacities that a person. When we educate, we want them to develop and reach their peak. This means the whole being. Therefore, it is education that not only focuses on memory, imagination or will but also embraces the person’s entire being and allows this being to develop to its fullest.

I believe this basically has four dimensions.

On the one hand, we have to develop the person’s physical dimension. This means healthy lifestyle habits, exercise, the bodily dimension of that person, care, hygiene, nutrition, lifestyle habits, sport and of course also care for the person’s sexual dimension.

The psychological dimension, whether emotional, mental or intellectual, also has to be developed. This is the ability to calculate, think, reflect and speculate. But it’s also the ability to organise emotions, to know how to prioritise them and even how to control certain toxic or negative emotions.

Then there is the social dimension. Each person should know how to interact with others, create solid bonds, establish trusting relationships, and, in short, create invigorating and noble relationships.

And then there is the spiritual dimension, which is also inherent to the person. Therefore, educating it means for that human being to develop a certain set of values, a certain type of ideals or purposes, and to reflect deeply on what beliefs they feel called to develop or even to accept.

What often happens, however, is that this education is reduced to a plan, even though we are all polygons with different facets. That is why I believe that educating in being means developing all the capacities latent in the person, and this cannot be done by a single human being: we need a community.

I believe that educating in being means developing all the capacities latent in the person, and this we need a community

To what extent is ‘becoming a better human being’ a question of context, time or culture? Can we assume that there is something immutable, universal and inherent to every human being that defines them qualitatively?

Yes, this is the debate between the permanent and the temporary. And in the educational process, we have to link the two dimensions. On the one hand, we have to train these children to be able to live in a complex world and therefore to know how to move around successfully in the technological world, the digital world, to understand languages well, to understand artefacts, robots, machines, biotechnologies…. All of this is circumstantial, contextual. Schools have to encourage this because we want them to adapt to and act in the world and not be social outcasts or maladjusted.

Then there are certain elements that are universally permanent. For example, there are virtues that are essential and have to be developed, regardless of whether we are in the twelfth or the twenty-first century.

Therefore, there are temporary aspects and we have to be attentive to them. On the other hand, there is a series of qualities or virtues, which, if they have them, will allow them to govern their various facets as a human being, a professional, a parent and a friend.

You have written a lot about human virtues and values. What do you think about ethics education in schools? What values would you highlight as most important in today’s world?

The first thing I would like to say is that there is no such thing as a neutral education and there never has been, and anyone who puts it that way is being deceitful. All education has an axiological dimension; that is, it is the bearer of certain values or counter-values. And we very often convey them unconsciously. Consequently, there can be no purely objective education. Teachers always radiate what they have, and parents radiate their values to their children and to the whole extended family.

As for the second part of the question, what values or virtues should be fostered, I think there are three basic ones today. One is boldness, not to be intimidated and not to be afraid to move forward with life projects.

Another is flexibility or ductility. We are in an ever-changing, constantly transforming world, and we need children who are able to adapt to new and different environments. Therefore, rigidity is an obstacle.

We are in an ever-changing world and we need children who are able to adapt to new and different environments

And the last one, I believe that we need children who have a third virtue, which is compassion. This is the opposite of indifference. I believe that education should make us people who show solidarity, who are responsible, who do not close our eyes in the face of tragedy but who try to contribute our talent and commitment to improve other people’s quality of life.

I believe that this is basic education, that is, a school that does not consider this is a school that is out of touch with the twenty-first century. We need young people, we need entrepreneurs, we need people who are involved in the noble causes that the world is facing today.

We need young people, entrepreneurs, people who are involved in the noble causes that the world is facing today

Currently, there is much talk about the importance of ‘agency’ in order to act with a sense of purpose, to think critically, and to make intentional and informed decisions in order to take ownership of one’s life. To what extent is it important to ask oneself about meaning? What are the keys to doing so?

The question of meaning, purpose, objective, what you live for, is crucial. And sometimes that question becomes blurred. I believe that it is central in educational practice that a kid begins to ask themselves what they want to do with their lives, what is their purpose or objective, and if that purpose is viable or not, if it is noble or not, if it is aligned with their nature or simply totally disproportionate. This has to do with discernment, tutorial action and mentoring, and we do this when we educate as opposed to just informing.

Educating has to do with supporting a person as they develop their life project. Therefore, we have to help students to discern, to see what steps they have to climb to make it a reality, and to support them when they fail, because quite often the project does not come to fruition for a thousand reasons. When a person is engaged in an activity that fulfils them, they are very happy. Now, if they find that activity sterile, absurd, empty, meaningless, even if they make a very good living, they will not be not happy. They may be wealthy and live comfortably, but when we talk about fulfilment, we are talking about a life project that is meaningful in itself.

An important issue in education is the concept we have of human freedom. There is a lot of talk about free will and that to be free is to be able to choose what we want. What idea of freedom would it make sense to have in education?

The word ‘freedom’ is one of the most manipulated, altered and, I would even say, semantically reduced words.

One idea of freedom is free will, that is, the ability to choose between two or more options.

There are other more demanding levels of freedom. Being free means being able to determine one’s own life project, to embody one’s own vocation, in short, to realise one’s own dream. Has to do with a process that entails discipline, effort, continuity over time, tenacity and a great deal of sacrifice. Today we have an idea of freedom without sacrifice. And that’s a mistake.

There is one last idea of freedom, which is freedom as liberation, freedom from everything that subjugates you, enchains you, keeps you imprisoned. Many things keep us alienated, and many people suffer severely from the opinions of others; others are subjugated to drugs, alcohol, screens and other new addictions. This is not freedom; this is slavery or servitude.

I believe that, in this sense, when one frees oneself from remorse or resentment, one is much freer. And all this happens through the act of forgiveness.

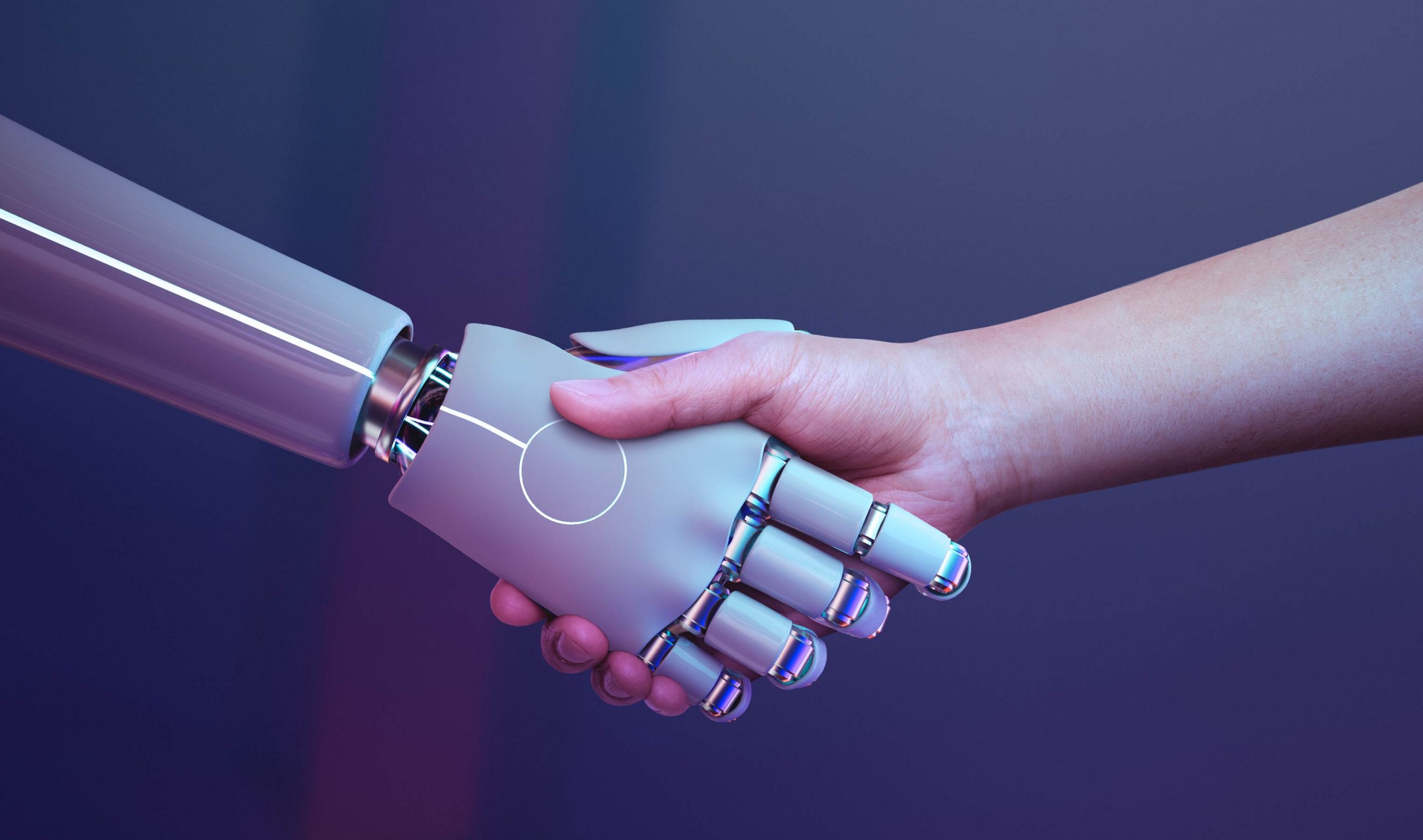

With the development of artificial intelligence (AI), many fears are cropping up about its increasing ability to replace human functions. To what extent do you think this is possible? What should the role of AI be in a truly human society centred on the full development of each person?

This is the big issue. We are kind of awed, moved and perplexed by the capabilities that these generative artificial intelligence systems are developing. We are increasingly finding that they have more capabilities, more features, that they are performing operations faster and are far superior to us in many fields, even though we have created this artificial intelligence ourselves.

What we need to do is take three actions in response. First, there is a need for proper regulation of artificial intelligence. That is, when you have an instrument with this potential, it is essential for it to be regulated. We also need transparency; we need to be told how it works, what algorithms are in place, what criteria they take into account.

And then there is a third key point, which is that it is essential to use it to help the most vulnerable.

We have to work hard on this so that artificial intelligence really becomes a system that serves the integral progress of the person, individual dignity and especially the most fragile and vulnerable among us. ‘Artificial intelligence must be a system at the service of the integral progress of the person, especially the most fragile and the most vulnerable’.