by Toni Gallemí

Throughout the last decades until today, there has been a special concern for the situation of women in society. Since then, numerous policies have been implemented in an attempt to promote and equalise their situation with that of men. In the field of education, this reality has been reversed in recent years to the point of generating a deep concern for the current situation of men.

Richard V. Reeves, author of the book “Of Boys and Men”, states that femininity is more defined by biology because of motherhood, while masculinity is defined more by social construct. “This is why masculinity tends to be more fragile than femininity”. To the question “When was the last crisis of femininity?” Reeves replies: “That’s right: never”. While we may agree or disagree with the answer, what Reeves suggests is that there is a crisis of masculinity today. And the truth is that there is evidence to back up his claim.

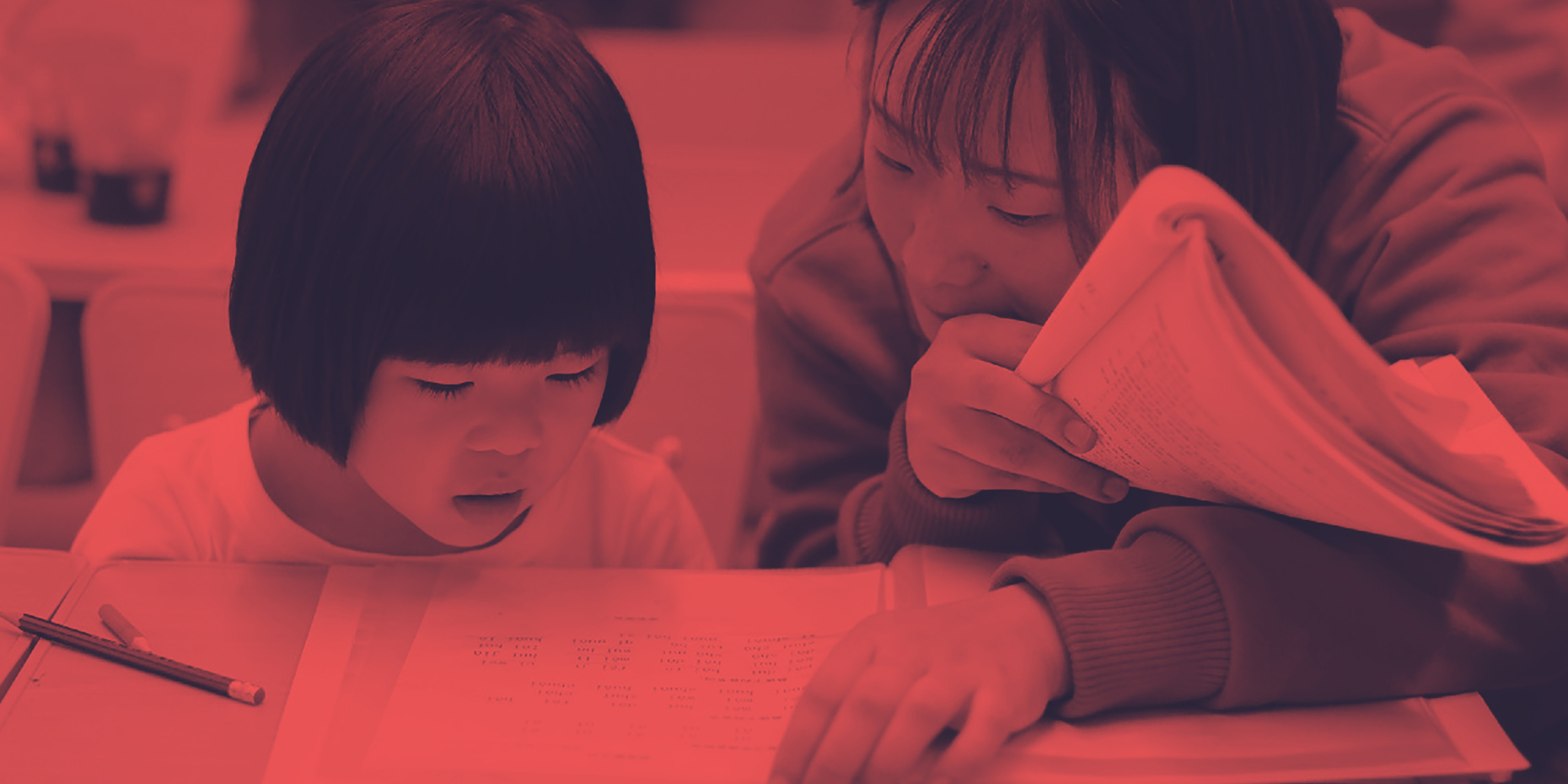

A recent report published by the OECD on gender gap between male and female in education has highlighted the precarious situation of men. The report highlights a number of points that are worth knowing: almost 60% of school dropouts are men, rising to over 70% in some countries; they study and read significantly less than girls; they spend more time playing video games and less time doing their homework at home. On the other hand, they lag far behind girls in literacy and, while it is true that they slightly outperform girls in STEM subjects, the margin is shrinking. Moreover, their behaviour and attitude to learning is very different; to some extent influenced by their later brain development, among other things.

Men’s behaviour and attitude to learning is very different; to some extent influenced by their later brain development

Educational and biological differences

Although Reeves focuses his data on the United States, many of the solutions he proposes are equally valid in other countries. The most significant contribution is his reference to biology: “Boys’ brains develop more slowly”. In fact, says Reeves, “it is fair to wonder if it is educational institutions, rather than boys, that are not functioning properly” when “almost one in four boys (23%) is categorized as having a developmental disability1. It is during puberty and adolescence that the greatest differences between the sexes are observed, and yet this recognition “has so far had no impact on [educational] policy”. Gender policies have focused on addressing women’s disadvantages without noticing men’s fragility, which has been accidentally diminished.

In the United States, as in the other OECD countries, graduations have also soared: 57% are awarded to women “and not just in stereotypically “female” subjects: women now account for almost half (47%) of undergraduate business degrees, for example, compared to fewer than 10% in 19702. Women also receive the majority of law degrees, up from about 5% in 1970”3. In addition, “the share of doctoral degrees in dentistry, medicine, or law being awarded to women has jumped from 7% in 1972 to 50% in 2019”4. The figures are similar to those of OECD countries, with more girls graduating than boys in all of them. Suddenly, says Reeves, working for gender equality means focusing on boys rather than girls.

Suddenly, says Reeves, working for gender equality means focusing on boys rather than girls

In contrast to the OECD, the English author, throughout his book, offers a variety of proposals (legislative, educational, economic) to try to compensate for the precariousness of men. For if the international organisation only “requires concerted efforts by parents, teachers and employers”, as the OECD proposes, this is not enough. Reeves specifies possible solutions to help them. But many of these solutions or proposals are only applicable if we understand that women and men are biologically different. “Sex differences in biology” says Reeves “shape not only our bodies, including our brains, but also our psychology”. In her book The Female Brain, scientist Louann Brizendine says that “if in the name of free will—and political correctness—we try to deny the influence of biology on the brain, we begin fighting our own nature”5. For example, men tend to be more aggressive, take more risks and have a higher sex drive than women 6, which generates behavioural differences, but not necessarily negative ones. On the other hand, men are somewhat more interested in things, while women are somewhat more interested in people7. This information is essential to understand the “failure” of boys in their education and academic development. Their development is late, as we have pointed out above; similarly, they need more physical activity than girls in their school time due to their hormonal development. Just by disregarding some of these data, education policies can become largely unfair by failing to discern between the needs of women and men, as is currently the case.

Many of these solutions or proposals are only applicable if we understand that women and men are biologically different

STEM and HEAL

The latest policies on gender parity, Reeves points out, should not be taken as an exact gender quota (50/50). On the contrary, precisely because of the differences outlined above, we should expect that in some areas there will be more men than women and vice versa. The English author insists that equal opportunities between the sexes must be sought, which does not imply effective equality in the results. On this note, “in 2018, two researchers, Gijsbert Stoet and David Geary, showed that in more gender-equal countries, such as Finland and Norway, women were less likely to take university courses in STEM subjects”8. This has been called the “STEM paradox”. Gender differences are greater in richer and more gender-equal countries. Armin Falk and Johannes Hermle also concluded that “a more egalitarian distribution of material and social resources enables women and men to independently express gender-specific preferences”9. But that’s not all, a similar study using different data came to the same conclusion. One of the authors, Petri Kajonius, points out that “another theory is that people in progressive countries have a greater desire to express differences in their identity through their gender”10.

A more egalitarian distribution of resources enables women and men to independently express gender preferences

Reeves summarises these results as follows: it’s not about meeting quotas, it’s not about having more or fewer women in STEM to balance the scales; it’s about them having the opportunity to freely decide what they want without being conditioned by adversities, whatever they may be. Olga Khazan puts it much better: “The upshot of this research is neither especially feminist nor especially sad. It’s not that gender equality discourages girls from pursuing science. It’s that it allows them not to if they’re not interested”11. The particularity of these statements is that they are influenced by a strong sense of justice, in the sense that they do not try to impose a balanced quota in favour of one sex, but a real equality of opportunities individually; in other words, the nature of the study is not imposing, but respectful of the freedom of each one.

It’s about them having the opportunity to freely decide what they want without being conditioned by adversities

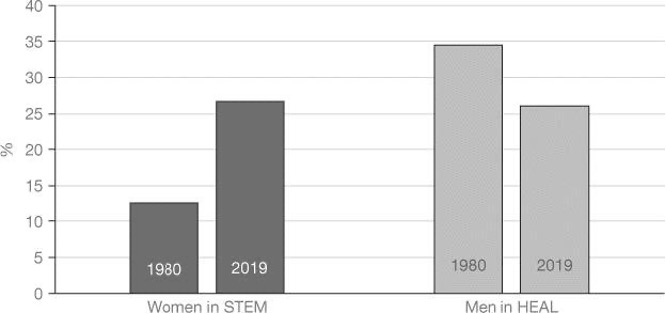

Reeves recalls that the proportion of men in HEAL (Health, Education, Administration, Literacy) professions is stubbornly low. In her book, Gloria Steinem makes the following observation: “Women are always saying, ‘We can do anything that men can do’. But men are not saying, ‘We can do anything that women can do’”12. In the same way as above, it is not about filling for the sake of filling, but about establishing real equality of opportunity. Reeves provides a significant graph on this issue: HEAL professions held by men have declined by 9 points from 1980 to 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Full-time employed workers ages 25–54. Source: Steven Ruggles and others, IPUMS USA: Version 11.0, 2021.

Given this fact, Reeves is adamant that “it is equally absurd to think that the 18% male share of social workers is an authentic representation of the true level of interest in the job among men, especially since it has halved since 1980”. Men’s choices are constrained when some jobs are labelled as “women’s jobs”. Moreover, according to calculation by Harvard professor David Deming, demand for jobs requiring social interaction increased by 12% between 1980 and 2012. While jobs with a lot of mathematics and less social interaction decreased by 3.3%13.

Men’s choices are constrained when some jobs are labelled as “women’s jobs”

On the other hand, Reeves emphasises the fact that women who receive STEM classes from a female professor get better grades and are more likely to graduate from university with a STEM degree14. And while there are no studies to prove this –Reeves does not provide any evidence– the English author says there is no reason to think that it would not work the other way around: male teachers teaching HEAL subjects would increase the number of boys interested in the professions, as well as will eliminate stereotypes of “jobs for women”. Low pay is another reason why men choose to go into other professions.

Some of Reeves’ proposals

Several of the solutions the author offers to solve some of these problems can be shocking. On the one hand, because of the late brain development status of males, Reeves proposes that boys should start school a year later to balance their maturity with that of girls a year younger. This would blur the obvious differences in their biological development and early literacy deficits. It also suggests that “among candidates for teaching posts in health and education, a 2:1 preference should be given to male applicants”. It could be seen as a gender discriminatory measure but, says Reeves, “It is in fact the same preference that is currently given to female tenure-track professors in STEM fields” (note that Reeves is talking about what is happening in the United States). Another of the author’s proposals is none other than investment: he points to the state and foundations to encourage them to reverse this situation through financial investment(scholarships, advertising, salaries).

Reeves proposes that boys should start school a year later to balance their maturity with that of girls a year younger

Richard V. Reeves has been the talk of the town for the boldness of his proposals, which have not gone unnoticed. The full name of his book is “Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Men is Struggling, Why It Matters and What to Do about It”.