by Toni Gallemí

The OECD has recently published a report on the persistence of gender gaps in education and its subsequent effects in the labour market. The latest publications of PIAAC (Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies), PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) and EAG (Education at a Glance) have been used for the study.

During the period between 2000 and 2020, more women have completed secondary and tertiary education. Much of this study has focused on the adolescence of young men and women and has highlighted the superior performance of girls in reading and the slight superiority of boys in mathematics.

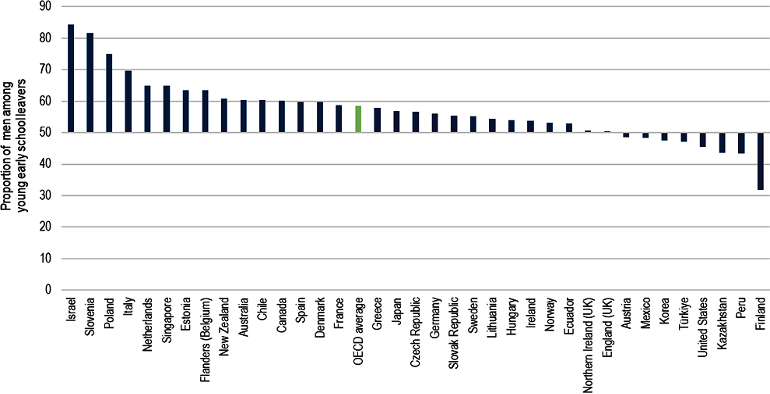

While there is good reason to celebrate women’s progress in education, it seems that these results may be tainted by the comparison with boys who, according to the report, perform much worse than girls. The reasons for this low academic performance are many, says the OECD, but differences in behaviour between men and women and their respectives attitudes towards learning have a big impact. According to PIAAC, 58% of school leavers between the ages of 18 and 24 are men. In countries such as Italy, Poland, Israel and Slovenia, the percentage exceeds 70% (figure 1). Ath this age, students are in the midst of adolescence: they are seeking independence from their parents and social acceptance of their friends has a powerful influence on their behaviour. In addition, numerous evidence suggests that boys adopt a concept of masculinity that is indifferent to authority and academic work.

Figure 1. Proportion of males among early school leavers. https://doi.org/10.1787/34680dd5-en

Underachievement is influenced differences in behaviour between men and women and attitudes to learning

With regard to their behaviour and attitudes towards learning, it has been shown that boys spend less time doing homework. And although this demonstration is not causal, the study points out that it is symptomatic:doing homework reinforces what they have learned or it simply persists as a sign of commitment to their obligations (Klauda and Guthrie, 2014). An earlier report dated in 2012 and conducted by PISA, concluded that time spent on homework is positively related to student performance (OECD, 2014). In 2018, PISA provided another study based on 32 countries and economies. Students were asked how much they studied outside school: 73% of girls had studied more than one hour the day before the test compared to the 64% of boys (OECD, 2019). So, what is done outside of school is indicative of students’ performance.

Doing homework reinforces what they have learned or it simply persists as a sign of commitment to their obligations

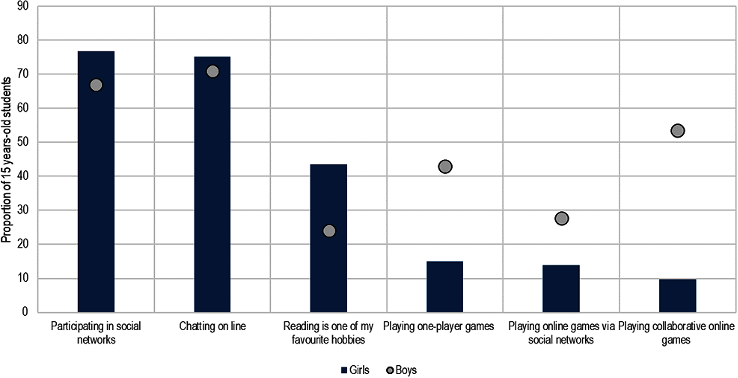

Another notable feature is time spent reading, as it has proved previous evidence: there is a strong correlation with high performance for those who spent time reading (Guthrie, Schafer and Huang, 2001; Mol and Jolles, 2014; OECD, 2015). “Students who enjoy reading, and make it a regular part of their lives, are able to improve their reading skills through practice. Better readers tend to read more because they are more motivated to read, which, in turn, leads to improved vocabulary and comprehension skills” (Sullivan and Brown, 2015). According to OECD data, among 15-year-olds, 44% of girls enjoy reading (“Reading is one of my favourite hobbies”), while for boys it is less than 25%. In addition, 60% of boys agreed that “I read only to get information that I need”, compared to 39% of girls (OECD, 2019).

Previous evidence has proved there is a strong correlation with high performance for those who spent time reading

In the digital era, technologies are a central element in the development and evolution of young people. The report points out that, outside school hours, boys spend much more time using technology for leisure purposes. “With children having greater access, and at ever-younger ages, to digital devices, teenagers’ online activities are increasingly unsupervised”. The proportion of girls using digital devices every or almost every day is much higher than boys, and they were slightly more likely to do so for online chatting. However, the biggest gap relates to video games. “On average across OECD countries, 53% of 15-year-old boys, but only 10% of girls that age reported that they play collaborative online games every day or almost every day” (figure 2) (OECD, 2019).

Figure 2. Proportion of 15 years-old students. https://doi.org/10.1787/34680dd5-en

53% of 15-year-old boys, but only 10% of girls that age reported that they play collaborative online games

Similar to boys’ underachievement, there may be many possible reasons for the under-representation of high-performing girls in mathematics. According to the report, girls are generally less confident than boys and also more likely to express strong feelings of anxiety. “In 70 countries and economies that participated in PISA 2018, girls reported more often, and to a larger extent, than boys, fear of failure” (OECD, 2019). Despite this lack of self-confidence, they tend to be much more motivated to do well in school and to believe that doing well is important. They also fear, more than boys, the negative judgements that may be made of them. The OECD believes that this fear of failure and lack of confidence in their abilities is often related to gender stereotypes faced at home, which are then reinforced with such biases, consciously or not, by their teachers (OECD, 2015).

Girls tend to be much more motivated to do well in school and to believe that doing well is important

Some OECD proposed conclusions

OECD stresses that reducing the gender gap does not require major reforms or expensive investments. On the contrary, it calls for profound efforts by parents, teachers and employers to be aware of their own stereotypical biases and thus provide equal opportunities for boys and girls to succeed (Schleicher, 2019).

Parents and teachers can help build and strengthen girls’ confidence in their own STEM skills and overcome anxiety. Improving and encouraging girls’ participation in mathematics and technology activities is crucial. Even the use of video games and technology to develop certain skills can be helpful, concludes the report, but the time of use must be controlled so that it does not have a negative impact on academic results. It is important to motivate girls to be more interested in maths and science and to encourage boys to read more. Hence, gender bias and stereotypes must be eliminated.

“Governments, schools and the private sector need to explore cooperation strategies (…) in order to increase girls’ interest in science-related subjects and boys’ interest in the humanities and arts-related subjects”.

References:

Encinas-Martín, M. and M. Cherian (2023), “Gender, Education and Skills: The Persistence of Gender Gaps in Education and Skills”, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/34680dd5-en.